Illustration Friday's theme this week is "wilderness." Okay, so this is a great one for me. I've spent quite a bit of time thinking about the wild, and I recognize the problems with it as a concept. Namely, we have a lot of romanticized notions of wilderness and what it means. Orginally, the concept referred to something unpleasant -- and so is etymologically linked to words like "bewilder." The Puritans saw the wilderness as a site of evil and danger, something to be tamed (like all "baser nature," internal or external). It took visionaries like Romantic poets and early American nature writers to see in the wilderness the sublime, that mix of awe and wonder at once terrifying and spiritually uplifting.

Today, several environmental thinkers posit that our perceptions of wilderness get in the way of meaningful environmental management more than they motivate it. Folks like

William Cronon and

Neil Evernden posit that our received notions of wilderness are more social construction than actual nature. Cronon notes that in the US, we tend to equate wilderness with the absence of humans, and in the process conveniently erase the humans that lived here before European colonization. Evernden cautions that many neophyte ecologists tend to focus on the happy "light" side of wilderness by emphasizing harmony and balance and downplaying the shadow side of all that -- including predation, parasitism, disease, etc. Both (and others) suggest that the evocation of wilderness is often a problematic call for preservation that fails to recognize that nature is always about change.

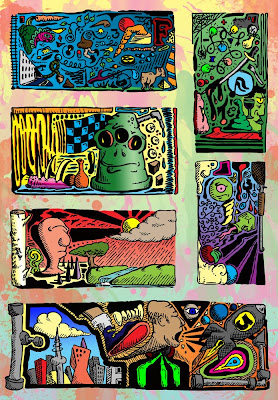

So what is "wilderness," given all this history and critique? For me, it is about systems of relationship. It's about organisms in relationships, be those relationships predatory, parasitic, symbiotic, nurturing, or what have you. Wilderness is an "organic" system, by which I mean both living and emergent/unplanned. This conception allows us to consider humans as both a part of wilderness (nature) and apart from it. The first half of that observation is easy -- we cannot escape it, it's all around us, and it supports us. But humans also create, with purpose, their own complex systems (towns, buildings, farms, ranches, factories, etc.) -- and those systems often compete with wilderness systems. The result of that competition is often bad for the wilderness, although occasionally wilderness "wins." More importantly, wilderness adapts from the competition, although perhaps a bit more slowly than human systems do.

The ecological systems we designate "wilderness" have developed over eons. They represent incredible diversity that still extends beyond our capacity to catalog let alone comprehend. And much as we like to ignore it in the name of human "progress," those finely honed organic systems support us, making our life on this planet possible. We have yet to replicate the dynamic and intricate system of relationships that is a wild ecosystem. Perhaps, one day we will. But until we do, we are ill-served in the casual destruction of wilderness. If that sounds like a preservationist's ethic sneaking back in, so be it. Or maybe, just maybe, it's about humbly accepting our place in (and not above) these wild systems of relationship.